However, I ran into many difficulties while working in Sketchup as I believe anyone who has used Sketchup has. But you work through them, and with the help of the internet and a little patience and perseverance, you start to feel like you can do anything.

In the end, the model I created of Horaceville sits nicely into its Google Earth environment, but the job is not done! In exchange for the wonderful pictures and architectural plans of the house, the model has been promised to the Pinhey's Point Foundation. I hope they will be able to put it to good use somehow. I think it can be used to entice people into visiting the museum. It would be nice to be able to offer virtual tours of the museum available on the internet, especially since the museum is only open for about 4 months of the year. It might also be used to allow disabled visitors to experience the second floor in some capacity, if not in person.

The model is still under construction though. Here are some cross sections (thanks Nick C. for showing us how to do this!) of the house so far.

One of my goals in making the model was to gain an appreciation of what the house looked and felt like in its prime before it started to fall into ruin. I want to communicate this to museum patrons so that they can get a deeper appreciation for the history of the house, and I would like to make it interactive and engaging for anyone who visits my model.

I am still exploring ways to do this. We could just take pictures or a video tour of the completed model, narrate it, and either integrate it into the Pinhey's Point Foundation website or into the exhibits themselves, but I think we can do more. Interactivity is the way of the future and I want to future-proof my model as much as possible.

I want people to be able to walk through the model virtually and experience what the house might have been like in the past. A virtual living museum of sorts. So what are my options for making my vision into a reality?

Once I have uploaded the model to the SketchUp Warehouse, I will in theory be able to embed it into a website or blog post. Let's give it a try with an existing model in the Warehouse. Here is attempt #1.

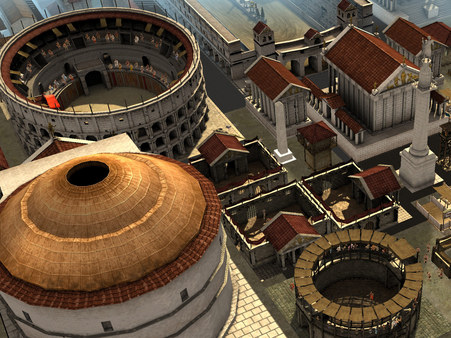

This is a model of another museum in Ottawa: the Bytown Museum. Situated next to the Ottawa Locks, this museum interprets the history of the development of Bytown. The building is of about the same age as Horaceville. As you can (hopefully) see, you can zoom in and out of the model and rotate it. Unfortunately, you can't view the inside of the building and the backdrop is static and boring. I would prefer my model to be geolocated and integrated into its virtual surroundings.

Another way to make a model available to the internet is to get it published in Google Earth, which makes it visible to people who search the address in Google Earth and Google Maps. But once again, you can't really view the inside with this option.

Right now, my best option seems to be LightUp for Sketchup, which allows you to save a number of scenes as .luca files and play them on the LightUp player that can be imbeded into a website. This would allow visitors to explore the model for themselves; unfortunately you still have to move from scene to scene to explore.

The option I am most excited about is that you can use SketchUp models as levels in open source video games, such as Left 4 Dead (learn how here). Although this may not be the best option for the historical visualization project, it is on my list of things to do over Christmas! I look forward to shooting zombies in the virtual 180 year old house.